Two Friends, One Lunch

Ask yourself how much time you spend really talking with friends or acquaintances who disagree with you ideologically? If you’re like most Americans, the answer is “hardly ever.” Healing the partisan divide in America doesn’t have to be a slog. It can be done over good food with an old friend or a family member who maybe you’ve been avoiding because you know how they voted. There’s lots of evidence that suggests that if we’d just spend more time with each other as human beings it would actually make a difference. We believe so strongly in the power of looking people in the eye while you break bread that we’ll mail you two free Flying Pig Bumper Stickers (one for you, one for your friend) if have a lunch and write us about it. Swag + Not the same boring ideas. Win.

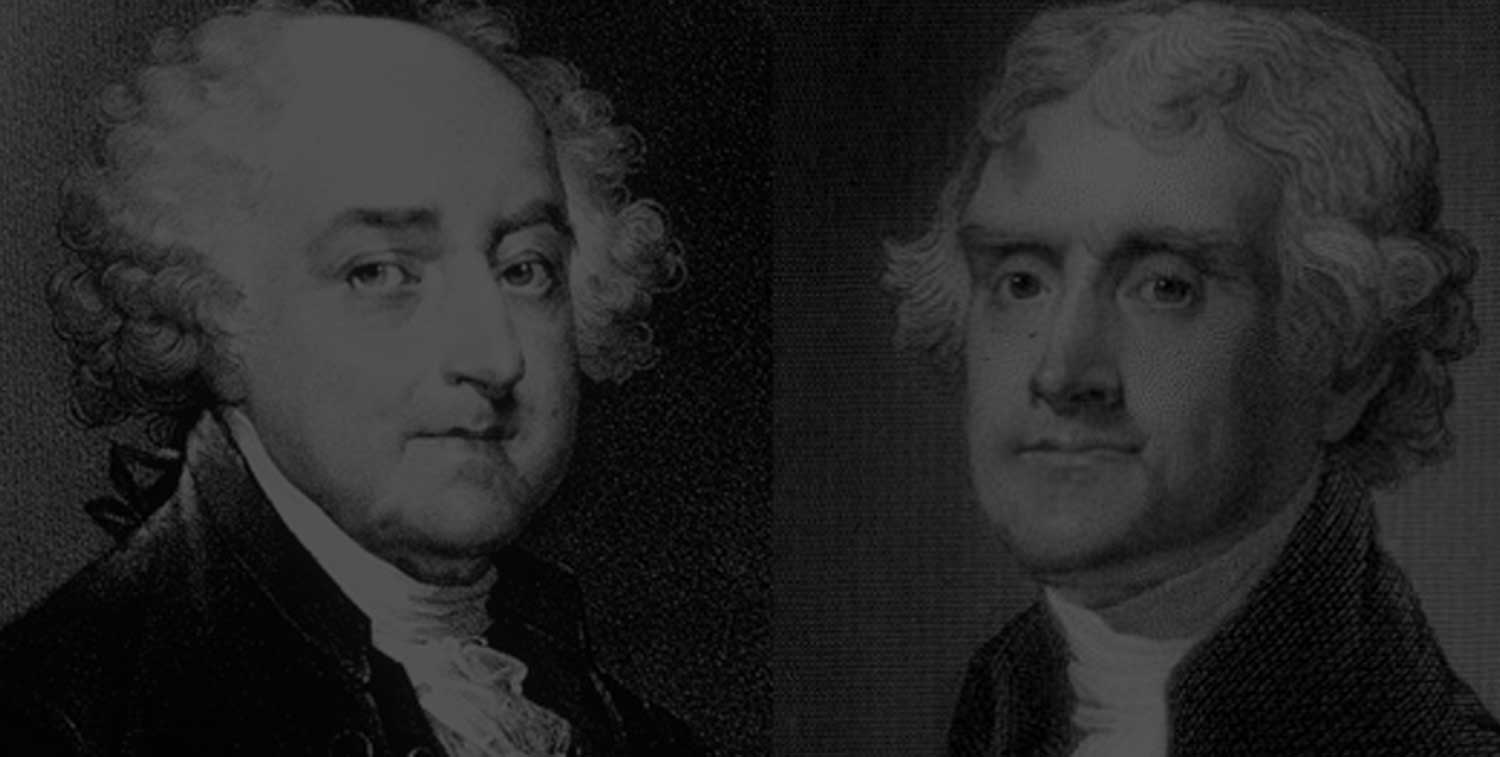

Here’s a little inspiration about a friendship that might just have been like yours – They left us this great story, we think we ought to run with it.

A Founding Tale: “Let Friendship Redeem the Republic”

“…You and I ought not to die until we have explained ourselves to each other.”

So began the late-life correspondence between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, the founding fathers described in the recent HBO mini-series “John Adams” as “the north and south poles of our revolution.”

Once friends, differences in opinion and political competition had taken a toll.

They, like others in the founders’ generation, had deep philosophical disagreements. But as they went about the business of building a country, an endeavor that if unsuccessful would surely lead to their hanging, they hardly had the luxury to stop talking to each other.

“…You and I ought not to die until we have explained ourselves to each other.” — From John Adams end-of-life letters to lifelong political foe Thomas Jefferson

Despite the differences between them and the odds against them, the founders managed to cobble together their opus – and ours – the Constitution, which despite all probability still guides this diverse group of people forward together.

But, alas, “politics ain’t beanbag” and two election cycles later, Jefferson and Adams had no tolerance for one another.

Fast-forward a couple of centuries and most of us are likely to relate to the fix Adams and Jefferson found themselves in. We, like they, have deep disagreement with – and sometimes little tolerance for – one another.

The two founders ultimately died friends, having given history the gift of their final correspondence. They died on the same day, July 4th, 50 years to the day after the nation they built was born.

“Whether you or I were right,” Adams had written to Jefferson, “posterity must judge. Yet I ask of you, who shall write the history of our revolution?”

The philosophical descendants of Jefferson and Adams are alive and well today in us, in this amazing American experiment “in the course of human events.”

And we are still writing the history of their revolution.

Like the founders, we hardly have the luxury to stop talking to each other. — Liz Joyner

Patricia Nelson Limerick: “It’s Surely Time for Lunch”

We read from Nelson’s New York Times column “Dining with Jeff” at our very first Village Square dinner in 2006. Nelson writes of her husband and the John Adams quote “…You and I ought not to die until we have explained ourselves to each other”:

I fell in love with this quotation 30 years ago, about the same time that I fell in love with Jeff Limerick, and for some of the same reasons. Honest, self-aware and articulate, Jeff made “explaining himself” into an art form, but his performance soared past his fellow mortals when it came to the tougher side of this transaction. Jeff had a genius for listening and giving people the best opportunity to explain themselves and to become his friend.

On Feb. 1, 2005, Jeff died of a stroke. Having trained with a master, I carry on with the methods I learned from him.

When I find myself puzzled and even vexed by the opinions and beliefs of other people, I invite them to have lunch. Multiple experiments have supported what we will call, in Jeff’s honor, the Limerick Hypothesis: in the bitter contests of values and political rhetoric that characterize our times, 90 percent of the uproar is noise, and 10 percent is what the scientists call “signal,” or solid, substantive information that will reward study and interpretation. If we could eliminate much of the noise, we might find that the actual, meaningful disagreements are on a scale we can manage.